… with all of the storm activity in the East and Central Pacific lately, it’s a question I’ve gotten from A LOT of people over the last two weeks. More specifically, people have been asking if two hurricanes can merge to form a “super hurricane.” To answer this question I interviewed my personal weather guru, Honolulu National Weather Service Forecaster Robert Ballard. He’s a wealth of information and always available to answer my crazy weather questions. Thank you Bob! By the way, all of the forecasters at the Honolulu office of the National Weather Service deserve huge kudos for the amazing job they do for Hawaii every single day – and of course, when we’re dealing with severe weather too.

A simple google search of “merging hurricanes” will bring up the Fujiwhara effect. I remember reading about this in my meteorology books when I was immersed in “weather land” to get my broadcast meteorology certification. The photos blew me away – I know that tropical cyclones occasionally “run into each other” by slowly spiraling inward toward each other - but the details of it were really just touched upon in class… so I turned to my weather guru for the answers.

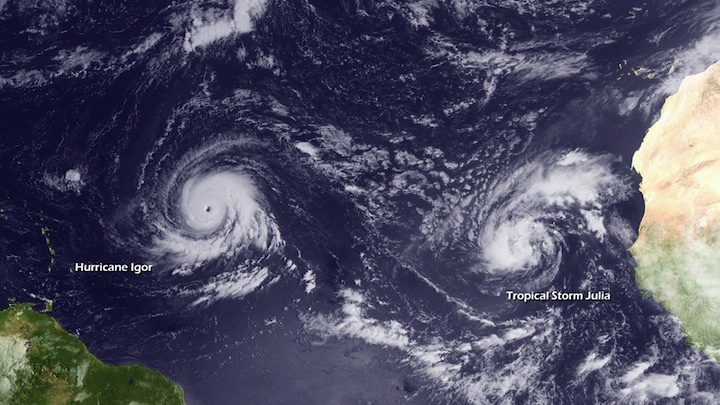

PC: NOAA PHOTO LIBRARY – Hurricane Igor and Tropical Storm Julia showing Fujiwhara Effect interaction.

How can tropical systems interact?

“Cyclones can interact in a few different ways… if they are both tropical cyclones, then yeah the movement can be a Fujiwhara. Generally if they are that close, one cyclone is usually dominant over the other and the other one will weaken. Sometimes, if they are near the same strength, then both cyclones will sort of be limited somewhat in intensity with neither one really taking off.”

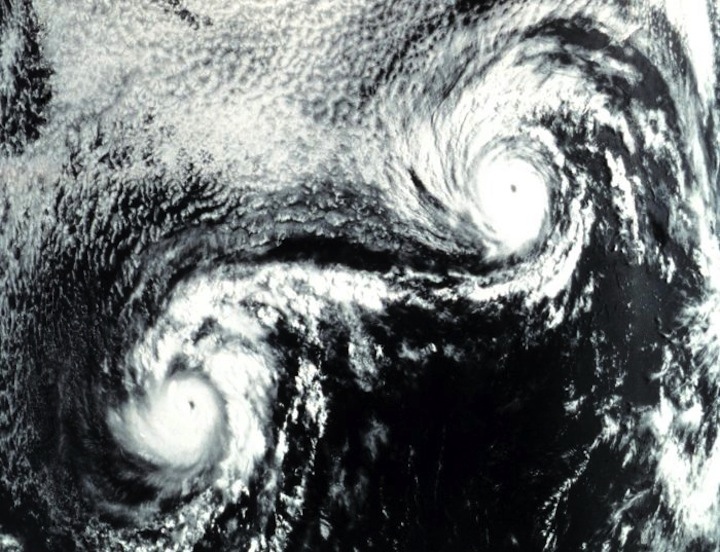

Very intriguing – at least for a weather geek like me – so I decided to dust off my meteorology books and do some research. The Fujiwhara effect is “the tendency of two nearby tropical cyclones to rotate cyclonically about each other.” The effect is named after Dr. Sakuhei Fujiwhara, who was the Chief of the Central Meteorological Bureau in Tokyo, Japan at the time. He initially described it in a 1921 paper about the motion of vortices in water. He noticed that if two vortices of the same size, strength and direction of spin approached each other, they would spin about a common point halfway between them. The National Weather Service defines it as “A binary interaction where tropical cyclones within a certain distance (300-750 nm depending on the sizes of the cyclones) of each other begin to rotate about a common midpoint.” In laymen’s terms – I suppose you could say it’s the tendency for two tropical cyclones to “merge” or orbit around each other when they get 350 – 850 miles apart.

Here are a few examples I found in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Joint Typhoon Warning Center files…

The video below shows Fujiwhara interaction between typhoon Pat and Tropical Storm Ruth in the west Pacific during the 1994 season. (The Fujiwhara effect is more common in the western Pacific than the eastern or central Pacific.)

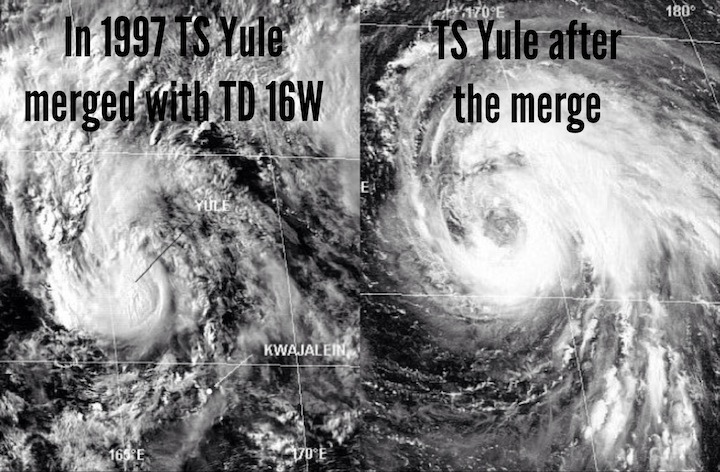

According to a Joint Typhoon Warning Center report, in August of 1997 Tropical Storm Yule and Tropical Depression 16W merged. TD 16W was horizontally sheared and swept into the intact circulation of Yule. Based on their analysis, JTWC decided the merged system would retain the name Yule. Click HERE for a link to Wikipedia’s list of Fujiwhara interactions observed in the past. Pretty interesting!

Are there any other ways that a tropical cyclone might interact with a weather feature?

“Yes. There are also occasions when a tropical cyclone might merge or be absorbed by a baroclinic system – a mid-latitude system with a cold front and a warm front – and can cause the baroclinic system to blow up very rapidly in certain instances; i.e. The “Perfect” Storm.”

Have you ever seen this effect in the Central of Eastern Pacific?

“I don’t think I’ve seen an instance where two tropical cyclones merged. Generally they maintain 10-15 degrees of seperation. If they don’t, then one usually falls apart pretty quickly.”

In fact, the final merging of two storms is actually not that common. However, as two storms approach one another they can influence each others tracks and intensity. Two storms of similar size could interact – spinning around each other – and eventually escape each others hold but usually, the end result is a kind of “survival of the fittest” – as Bob expressed earlier – in which the weaker storm will continue to weaken as subsidence from the stronger storm leads to it dissipating before they even get a chance to merge.

Another way two tropical cyclones (in close proximity) can affect each other is dependent on the track that each takes. If the second storm follows closely in the wake of the first, it’s likely to be passing over cooler waters that were mixed up by the passage of the first storm which could also help to weaken the system.

So, it seems the headline “Two hurricanes merge to form Super Hurricane” – though not impossible – is in reality quite far-fetched.